Does openness theology teach Korihor's philosophy that 'no man can know of anything which is to come' (Alma 30:13)?

J. Hathaway

- 5 minutes read - 1015 wordsKorihor was one of three named teachers of religions against Christ in the Book of Mormon. He was the only one specifically called an Anti-Christ in Alma 30:6 and 12. His primary argument against Christ was that we could not know the future. His was hyper-focused presentism that was equally cynical of historical tradition as well. His argument against Christ sits on the concept that any knowledge future was impossible. Those that proposed such a knowledge were ‘frenzied’. Alma 30:13-16 states;

O ye that are bound down under a foolish and a vain hope, why do ye yoke yourselves with such foolish things? Why do ye look for a Christ? For no man can know of anything which is to come. Behold, these things which ye call prophecies, which ye say are handed down by holy prophets, behold, they are foolish traditions of your fathers. How do ye know of their surety? Behold, ye cannot know of things which ye do not see; therefore ye cannot know that there shall be a Christ. Ye look forward and say that ye see a remission of your sins. But behold, it is the effect of a frenzied mind; and this derangement of your minds comes because of the traditions of your fathers, which lead you away into a belief of things which are not so.

Korihor’s argument seems especially weak if he were arguing about anything in the future. Once a tree has been cut, can we not know that it will fall to the ground? Was he saying that nothing at any period in the future is knowable? What are the ’things’ he references? Answering these questions can help us understand openness theologian’s views on a contingent future.

What are things?

The word ’thing’ is pretty vague. My children have blamed me more than once of poor directions when I tell them, ‘Go into the garage and open the thing on the shelf and then bring me the green thing on the top.’ In our modern language, we most often use the word ’thing’ to specify an item or object. However, according to Webster’s 1828 dictionary the general significance of the word in Scriptures is ‘An event or action; that which happens or falls out, or that which is done, told or proposed.’ to which they then provide a list of examples from the Bible.

- And the thing was very grievous in Abraham’s sight, because of his son. Genesis 21:11.

- Then Laban and Bethuel answered and said, the thing proceedeth from the Lord. Genesis 24:50.

- And Jacob said, all these things are against me. Gen 42.

- I will tell you by what authority I do these things. Matthew 21:24.

This concept of an event or action is Korihor’s argument. He argues that no man can know of the atoning event that Christ would perform in the future because the future is not knowable.

What is the future?

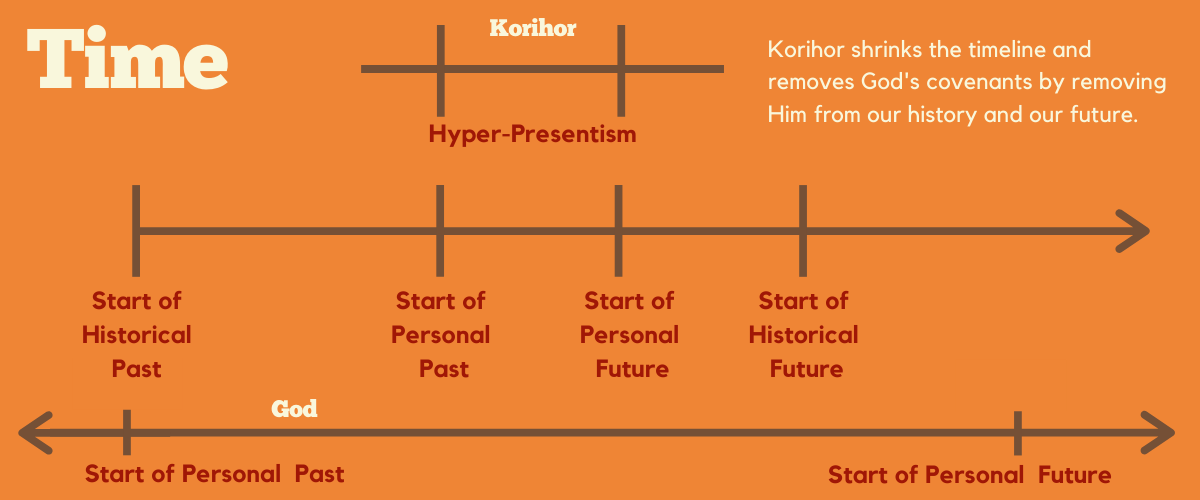

We can’t know any event in any part of the future? If we take his statement at face value, this seems to be his argument - ‘No man can know of anything which is to come’. However, the broader context of his argument is that we cannot know facts that are in the ‘historical future’ instead of just those events that are in his ‘personal future.’ You may ask, ‘What is the historical future?’ In Time Warped by Claudia Hammond, she explains Thomas Cottle’s investigations into how we perceive time. One of his experiments asked individuals to place the predefined text and vertical bars on the middle timeline of the figure below; he defined the text as the start of the historical past, the personal past, the personal future, and the historical future. Look at the chart to see a depiction of the historical future relative to other points in a timeline.

The strength of Korihor’s argument lies in the discussion about the historical past and historical future. Those events in the historical past are irrelevant because they were based on people that were ‘frenzied’1, and those events in the historical future were unknowable and, therefore, not true. So, we shouldn’t pick on him for the personal or near future concept of nothing being knowable. However, Can no events be known in the historical future?

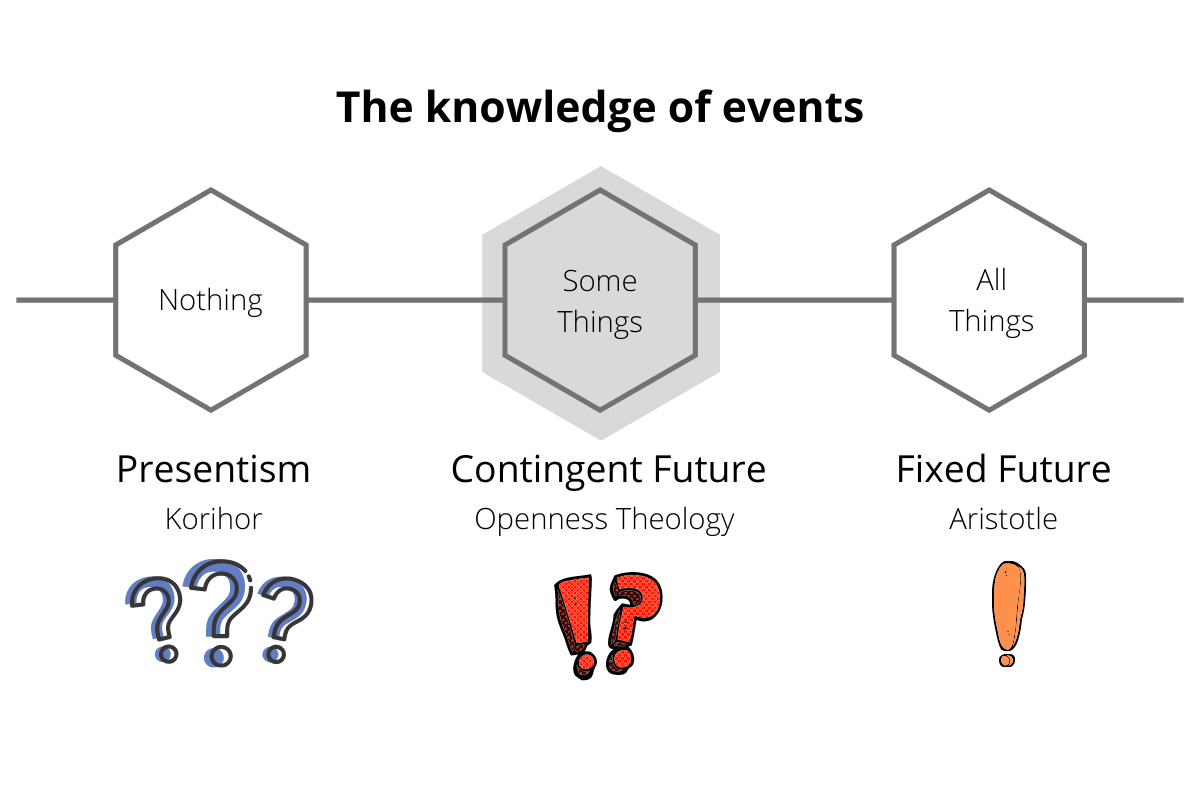

Nothing, All things, Somethings

Korihor’s belief that nothing can be known in the historical future is the key element. When openness theologians talk about a contingent future, they are not saying that nothing is knowable. A belief in a historical future that is entirely unknowable contradicts God’s agency, as Korihor argued. A belief in a historical future that is fixed contradicts the agency of man. Like Goldilocks, the place in the middle where some events are known, and some events are unknown provides space for man’s agency and the agency and omnipotence of God.

For example;

- As the Book of Mormon and Isaiah testify, the knowledge of Jesus Christ’s atonement is fixed throughout time. That is the great covenant that we can look to for salvation.

- The second coming event is fixed, but the timing of the second coming doesn’t need to be fixed.

- That God will reach out to us in love is promised and, therefore, a fixed event. That we will return our love is contingent on our agency.

The idea that nothing in the historical future is knowable is a primary teaching of an Anti-Christ. It is precisely this type of instruction that cuts at the eternal aspects of God’s covenants. God has covenanted with His people in the past, and He can keep His promises in the future. Openness theologians confirm that God does know some events that will happen in the future, but that other events are contingent on our agency.

-

This argument about the past is part of what scares me with our current backlash to US history. A blanket statement that everyone in the historical past was ‘frenzied’ and therefore shouldn’t be trusted or remembered for any positive value is too far. We need to value our history. We shouldn’t make it too frenzied or too rosy. ↩︎